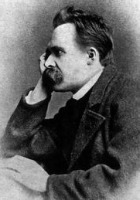

Parable Of The Madman Poem by Friedrich Nietzsche

Parable Of The Madman

Have you not heard of that madman who lit a lantern in the bright morning

hours,

ran to the market place, and cried incessantly:

'I seek God! I seek God!'

As many of those who did not believe in God

were standing around just then,

he provoked much laughter.

Has he got lost? asked one.

Did he lose his way like a child? asked another.

Or is he hiding?

Is he afraid of us? Has he gone on a voyage? emigrated?

Thus they yelled and laughed.

The madman jumped into their midst and pierced them with his eyes.

'Whither is God?' he cried; 'I will tell you.

We have killed him--you and I.

All of us are his murderers.

But how did we do this?

How could we drink up the sea?

Who gave us the sponge to wipe away the entire horizon?

What were we doing when we unchained this earth from its sun?

Whither is it moving now? Whither are we moving?

Away from all suns?

Are we not plunging continually?

Backward, sideward, forward, in all directions?

Is there still any up or down?

Are we not straying, as through an infinite nothing?

Do we not feel the breath of empty space?

Has it not become colder? Is not night continually closing in on us?

Do we not need to light lanterns in the morning?

Do we hear nothing as yet of the noise of the gravediggers

who are burying God?

Do we smell nothing as yet of the divine decomposition?

Gods, too, decompose.

God is dead.

God remains dead.

And we have killed him.

'How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers?

What was holiest and mightiest of all that the world has yet owned has bled

to death under our knives: who will wipe this blood off us?

What water is there for us to clean ourselves?

What festivals of atonement, what sacred gamesshall we have to invent?

Is not the greatness of this deed too great for us?

Must we ourselves not become gods simply to appear worthy of it?

There has never been a greater deed; and whoever is born after us -

For the sake of this deed he will belong to a higher history than all

history hitherto.'

Here the madman fell silent and looked again at his listeners;

and they, too, were silent and stared at him in astonishment.

At last he threw his lantern on the ground,

and it broke into pieces and went out.

'I have come too early,' he said then; 'my time is not yet.

This tremendous event is still on its way, still wandering;

it has not yet reached the ears of men.

Lightning and thunder require time;

the light of the stars requires time;

deeds, though done, still require time to be seen and heard.

This deed is still more distant from them than most distant stars -

and yet they have done it themselves.

It has been related further that on the same day

the madman forced his way into several churches

and there struck up his requiem aeternam deo.

Led out and called to account, he is said always to have replied nothing

but:

'What after all are these churches now

if they are not the tombs and sepulchers of God?'

Die fröhliche Wissenschaft. Von Friedrich Nietzsche 125. Der tolle Mensch. — Habt ihr nicht von jenem tollen Menschen gehört, der am hellen Vormittage eine Laterne anzündete, auf den Markt lief und unaufhörlich schrie: „Ich suche Gott! Ich suche Gott! “ — Da dort gerade Viele von Denen zusammen standen, welche nicht an Gott glaubten, so erregte er ein grosses Gelächter. Ist er denn verloren gegangen? sagte der Eine. Hat er sich verlaufen wie ein Kind? sagte der Andere. Oder hält er sich versteckt? Fürchtet er sich vor uns? Ist er zu Schiff gegangen? ausgewandert? — so schrieen und lachten sie durcheinander. Der tolle Mensch sprang mitten unter sie und durchbohrte sie mit seinen Blicken. „Wohin ist Gott? rief er, ich will es euch sagen! Wir haben ihn getötet, — ihr und ich! Wir Alle sind seine Mörder! Aber wie haben wir dies gemacht? Wie vermochten wir das Meer auszutrinken? Wer gab uns den Schwamm, um den ganzen Horizont wegzuwischen? Was taten wir, als wir diese Erde von ihrer Sonne losketteten? Wohin bewegt sie sich nun? Wohin bewegen wir uns? Fort von allen Sonnen? Stürzen wir nicht fortwährend? Und rückwärts, seitwärts, vorwärts, nach allen Seiten? Gibt es noch ein Oben und ein Unten? Irren wir nicht wie durch ein unendliches Nichts? Haucht uns nicht der leere Raum an? Ist es nicht kälter geworden? Kommt nicht immerfort die Nacht und mehr Nacht? Müssen nicht Laternen am Vormittage angezündet werden? Hören wir noch Nichts von dem Lärm der Totengräber, welche Gott begraben? Riechen wir noch Nichts von der göttlichen Verwesung? — auch Götter verwesen! Gott ist tot! Gott bleibt tot! Und wir haben ihn getötet! Wie trösten wir uns, die Mörder aller Mörder? Das Heiligste und Mächtigste, was die Welt bisher besass, es ist unter unseren Messern verblutet, — wer wischt dies Blut von uns ab? Mit welchem Wasser könnten wir uns reinigen? Welche Sühnfeiern, welche heiligen Spiele werden wir erfinden müssen? Ist nicht die Grösse dieser Tat zu gross für uns? Müssen wir nicht selber zu Göttern werden, um nur ihrer würdig zu erscheinen? Es gab nie eine grössere That, — und wer nur immer nach uns geboren wird, gehört um dieser Tat willen in eine höhere Geschichte, als alle Geschichte bisher war! “ — Hier schwieg der tolle Mensch und sah wieder seine Zuhörer an: auch sie schwiegen und blickten befremdet auf ihn. Endlich warf er seine Laterne auf den Boden, dass sie in Stücke sprang und erlosch. „Ich komme zu früh, sagte er dann, ich bin noch nicht an der Zeit. Dies ungeheure Ereignis ist noch unterwegs und wandert, — es ist noch nicht bis zu den Ohren der Menschen gedrungen. Blitz und Donner brauchen Zeit, das Licht der Gestirne braucht Zeit, Taten brauchen Zeit, auch nachdem sie getan sind, um gesehen und gehört zu werden. Diese Tat ist ihnen immer noch ferner, als die fernsten Gestirne, — und doch haben sie dieselbe getan! “ — Man erzählt noch, dass der tolle Mensch des selbigen Tages in verschiedene Kirchen eingedrungen sei und darin sein Requiem aeternam deo angestimmt habe. Hinausgeführt und zur Rede gesetzt, habe er immer nur dies entgegnet: „Was sind denn diese Kirchen noch, wenn sie nicht die Grüfte und Grabmäler Gottes sind? “ —

Beautiful. Nietzsche, in this section of Thus spoke zarathustra is referring to the void brought by the realisation that the idea of a god is obsolete. Nietzsche acknowledged that the source of ethical values and numerous beliefs are grounded upon this notion. The people that the mad man addressed had already realised that god is dead, but they fail to see the implications of the realisation itself.

'God is dead' and atheism is for those who have not experienced the belief of the soul in people, which religions try to teach, so as madmen they go around thinking all could be as soulless as they are. But religions have also unfortunately tortured or killed non believers instead of converting and teaching them about God and having a soul. Each human has a soul that needs to develop with education, religion, relationships, intelligence, laws, etc.

This poem has not been translated into any other language yet.

I would like to translate this poem

da 'La Gaia Scienza'.. hmm.. I was 18 when I read Nietzsche's Die fröhliche Wissenschaft.. a ''whole life'' ago..