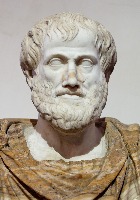

Aristotle

Aristotle Poems

Virtue, to men thou bringest care and toil;

Yet art thou life's best, fairest spoil!

O virgin goddess, for thy beauty's sake

...

Aristotle Biography

Aristotle (Greek: Ἀριστοτέλης, Aristotélēs) (384 BC – 322 BC) was a Greek philosopher, a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. His writings cover many subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, politics, government, ethics, biology, and zoology. Together with Plato and Socrates (Plato's teacher), Aristotle is one of the most important founding figures in Western philosophy. Aristotle's writings constitute a first at creating a comprehensive system of Western philosophy, encompassing morality and aesthetics, logic and science, politics and metaphysics. Aristotle's views on the physical sciences profoundly shaped medieval scholarship, and their influence extended well into the Renaissance, although they were ultimately replaced by Newtonian physics. In the zoological sciences, some of his observations were confirmed to be accurate only in the nineteenth century. His works contain the earliest known formal study of logic, which was incorporated in the late nineteenth century into modern formal logic. In metaphysics, Aristotelianism had a profound influence on philosophical and theological thinking in the Islamic and Jewish traditions in the Middle Ages, and it continues to influence Christian theology, especially Eastern Orthodox theology, and the scholastic tradition of the Catholic Church. His ethics, though always influential, gained renewed interest with the modern advent of virtue ethics. All aspects of Aristotle's philosophy continue to be the object of active academic study today. Though Aristotle wrote many elegant treatises and dialogues (Cicero described his literary style as "a river of gold"), it is thought that the majority of his writings are now lost and only about one-third of the original works have survived. Despite the far-reaching appeal that Aristotle's works have traditionally enjoyed, today modern scholarship questions a substantial portion of the Aristotelian corpus as authentically Aristotle's own. Aristotle was born in Stageira, Chalcidice, in 384 BC, about 55 km (34 mi) east of modern-day Thessaloniki. His father Nicomachus was the personal physician to King Amyntas of Macedon. Aristotle was trained and educated as a member of the aristocracy. At about the age of eighteen, he went to Athens to continue his education at Plato's Academy. Aristotle remained at the academy for nearly twenty years, not leaving until after Plato's death in 347 BC. He then traveled with Xenocrates to the court of his friend Hermias of Atarneus in Asia Minor. While in Asia, Aristotle traveled with Theophrastus to the island of Lesbos, where together they researched the botany and zoology of the island. Aristotle married Hermias's adoptive daughter (or niece) Pythias. She bore him a daughter, whom they named Pythias. Soon after Hermias' death, Aristotle was invited by Philip II of Macedon to become the tutor to his son Alexander the Great in 343 BC. Aristotle was appointed as the head of the royal academy of Macedon. During that time he gave lessons not only to Alexander, but also to two other future kings: Ptolemy and Cassander. In his Politics, Aristotle states that only one thing could justify monarchy, and that was if the virtue of the king and his family were greater than the virtue of the rest of the citizens put together. Tactfully, he included the young prince and his father in that category. Aristotle encouraged Alexander toward eastern conquest, and his attitude towards Persia was unabashedly ethnocentric. In one famous example, he counsels Alexander to be 'a leader to the Greeks and a despot to the barbarians, to look after the former as after friends and relatives, and to deal with the latter as with beasts or plants'. By 335 BC he had returned to Athens, establishing his own school there known as the Lyceum. Aristotle conducted courses at the school for the next twelve years. While in Athens, his wife Pythias died and Aristotle became involved with Herpyllis of Stageira, who bore him a son whom he named after his father, Nicomachus. According to the Suda, he also had an eromenos, Palaephatus of Abydus. It is during this period in Athens from 335 to 323 BC when Aristotle is believed to have composed many of his works.[5] Aristotle wrote many dialogues, only fragments of which survived. The works that have survived are in treatise form and were not, for the most part, intended for widespread publication, as they are generally thought to be lecture aids for his students. His most important treatises include Physics, Metaphysics, Nicomachean Ethics, Politics, De Anima (On the Soul) and Poetics. Aristotle not only studied almost every subject possible at the time, but made significant contributions to most of them. In physical science, Aristotle studied anatomy, astronomy, embryology, geography, geology, meteorology, physics and zoology. In philosophy, he wrote on aesthetics, ethics, government, metaphysics, politics, economics, psychology, rhetoric and theology. He also studied education, foreign customs, literature and poetry. His combined works constitute a virtual encyclopedia of Greek knowledge. It has been suggested that Aristotle was probably the last person to know everything there was to be known in his own time. Near the end of Alexander's life, Alexander began to suspect plots against himself, and threatened Aristotle in letters. Aristotle had made no secret of his contempt for Alexander's pretense of divinity, and the king had executed Aristotle's grandnephew Callisthenes as a traitor. A widespread tradition in antiquity suspected Aristotle of playing a role in Alexander's death, but there is little evidence for this. Upon Alexander's death, anti-Macedonian sentiment in Athens once again flared. Eurymedon the hierophant denounced Aristotle for not holding the gods in honor. Aristotle fled the city to his mother's family estate in Chalcis, explaining, "I will not allow the Athenians to sin twice against philosophy," a reference to Athens's prior trial and execution of Socrates. However, he died in Euboea of natural causes within the year (in 322 BC). Aristotle named chief executor his student Antipater and left a will in which he asked to be buried next to his wife)

The Best Poem Of Aristotle

Hymn To Virtue

Virtue, to men thou bringest care and toil;

Yet art thou life's best, fairest spoil!

O virgin goddess, for thy beauty's sake

To die is delicate in this our Greece,

Or to endure of pain the stern strong ache.

Such fruit for our soul's ease

Of joys undying, dearer far than gold

Or home or soft-eyed sleep, dost thou unfold!

It was for thee the seed of Zeus,

Stout Herakles, and Leda's twins, did choose

Strength-draining deeds, to spread abroad thy name:

Smit with the love of thee

Aias and Achilleus went smilingly

Down to Death's portal, crowned with deathless fame.

Now, since thou art so fair,

Leaving the lightsome air.

Atarneus' hero hath died gloriously.

Wherefore immortal praise shall be his guerdon:

His goodness and his deeds are made the burden

Of songs divine

Sung by Memory's daughters nine,

Hymning of hospitable Zeus the might

And friendship firm as fate in fate's despite.

Aristotle Comments

Aristotle Quotes

Rhetoric may be defined as the faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion.

Of the modes of persuasion furnished by the spoken word there are three kinds. The first kind depends on the personal character of the speaker; the second on putting the audience into a certain frame of mind; the third on the proof, provided by the words of the speech itself.

In making a speech one must study three points: first, the means of producing persuasion; second, the language; third the proper arrangement of the various parts of the speech.

Wit is educated insolence.

The moral virtues, then, are produced in us neither by nature nor against nature. Nature, indeed, prepares in us the ground for their reception, but their complete formation is the product of habit.

What the statesman is most anxious to produce is a certain moral character in his fellow citizens, namely a disposition to virtue and the performance of virtuous actions.

We praise a man who feels angry on the right grounds and against the right persons and also in the right manner at the right moment and for the right length of time.

Young men have strong passions and tend to gratify them indiscriminately. Of the bodily desires, it is the sexual by which they are most swayed and in which they show absence of control...They are changeable and fickle in their desires which are violent while they last, but quickly over: their impulses are keen but not deep rooted.

Good habits formed at youth make all the difference.

Plato is dear to me, but dearer still is truth.

God and nature do nothing in vain.

No great genius has ever existed without some touch of madness.

All men by nature desire knowledge.

For it is owing to their wonder that men both now begin and at first began to philosophize.... And a man who is puzzled and wonders thinks himself ignorant ...; therefore since they philosophized in order to escape from ignorance, evidently they were pursuing science in order to know, and not for any utilitarian end.

For as the eyes of bats are to the blaze of day, so is the reason in our soul to the things which are by nature most evident of all.

Every art and every inquiry, and similarly every action and choice, is thought to aim at some good; and for this reason the good has rightly been declared to be that at which all things aim.

For one swallow does not make a summer, nor does one day; and so too one day, or a short time, does not make a man blessed and happy.

Excellence, then, is a state concerned with choice, lying in a mean, relative to us, this being determined by reason and in the way in which the man of practical wisdom would determine it.

We make war that we may live in peace.

For though we love both the truth and our friends, piety requires us to honor the truth first.

If happiness, then, is activity expressing virtue, it is reasonable for it to express the supreme virtue, which will be the virtue of the best thing.

The generality of men are naturally apt to be swayed by fear rather than reverence, and to refrain from evil rather because of the punishment that it brings than because of its own foulness.

The life of mind is best and pleasantest for man, since mind more than anything else is man. This life therefore is also the happiest.

Excellence or virtue is a settled disposition of the mind that determines our choice of actions and emotions and consists essentially in observing the mean relative to us ... a mean between two vices, that which depends on excess and that which depends on defect.

Temperance is a mean with regard to pleasures.

Courage is a mean with regard to fear and confidence.

One kind of justice is that which is manifested in distributions of honour or money or the other things that fall to be divided among those who have a share in the constitution ... and another kind is that which plays a rectifying part in transactions.

Art is identical with a state of capacity to make, involving a true course of reasoning. All art is concerned with coming into being ... for art is concerned neither with things that are, or come into being, by necessity, nor with things that do so in accordance with nature.

Perfect friendship is the friendship of men who are good, and alike in excellence; for these wish well alike to each other qua good, and they are good in themselves.

Generally, about all perception, we can say that a sense is what has the power of receiving into itself the sensible forms of things without the matter, in the way in which a piece of wax takes on the impress of a signet ring without the iron or gold.

So, if we must give a general formula applicable to all kinds of soul, we must describe it as the first actuality [entelechy] of a natural organized body.

A sense is what has the power of receiving into itself the sensible forms of things without the matter, in the way in which a piece of wax takes on the impress of a signet-ring without the iron or gold.

Something is infinite if, taking it quantity by quantity, we can always take something outside.

Beauty depends on size as well as symmetry. No very small animal can be beautiful, for looking at it takes so small a portion of time that the impression of it will be confused. Nor can any very large one, for a whole view of it cannot be had at once, and so there will be no unity and completeness.

A tragedy is a representation of an action that is whole and complete and of a certain magnitude.... A whole is what has a beginning and middle and end.

A poet's object is not to tell what actually happened but what could or would happen either probably or inevitably.... For this reason poetry is something more scientific and serious than history, because poetry tends to give general truths while history gives particular facts.

Hence poetry is something more philosophic and of graver import than history, since its statements are rather of the nature of universals, whereas those of history are singulars.

So it is naturally with the male and the female; the one is superior, the other inferior; the one governs, the other is governed; and the same rule must necessarily hold good with respect to all mankind.

Man is by nature a political animal.

For as the interposition of a rivulet, however small, will occasion the line of the phalanx to fluctuate, so any trifling disagreement will be the cause of seditions; but they will not so soon flow from anything else as from the disagreement between virtue and vice, and next to that between poverty and riches.

Inferiors revolt in order that they may be equal, and equals that they may be superior. Such is the state of mind which creates revolutions.

The beginning of reform is not so much to equalize property as to train the noble sort of natures not to desire more, and to prevent the lower from getting more.

Whosoever is delighted in solitude is either a wild beast or a god.

The state is a creation of nature and man is by nature a political animal.

He who can be, and therefore is, another's, and he who participates in reason enough to apprehend, but not to have, is a slave by nature.

A constitution is the arrangement of magistracies in a state.

The government, which is the supreme authority in states, must be in the hands of one, or of a few, or of the many. The true forms of government, therefore, are those in which the one, the few, or the many, govern with a view to the common interest.

It is clearly better that property should be private, but the use of it common; and the special business of the legislator is to create in men this benevolent disposition.

Governments which have a regard to the common interest are constituted in accordance with strict principles of justice, and are therefore true forms; but those which regard only the interest of the rulers are all defective and perverted forms, for they are despotic, whereas a state is a community of freemen.

To the query, "What is a friend?" his reply was "A single soul dwelling in two bodies."